Moments in C.P. History - Number 8: Catherine de Medici

Eighth part of the series by Paul Melrose, from Februs 39

Catherine de Medici was born in 1519 in Auvergne and was

related via her maternal grandmother to the royal house of France. She was

orphaned when only a baby but her fortunes appeared to have changed when, still

only thirteen years old, she was given in marriage to Henry, the second son of

King Francis I of France. Much political intrigue had surrounded this match

because Pope Clement VII was Catherine’s uncle and the King had hoped, by this

marriage, to gain much influence in papal circles. However, when the Pope died

the year following the wedding, all Francis’ scheming with regard to marrying

off his son came to naught, thus Catherine became ‘disposable’ and was

consigned to obscurity for ten years even after Henry became King. The

humiliation she suffered was intense, having to pander to the whims of her

husband’s beautiful mistress, Diane of Poitiers, merely to retain some degree

of respect and authority. It is said that this experience coloured much of her

attitude in later life.

She became very powerful once Henry died in 1559 and her

son Francis II took the throne. He was the husband of Mary Stuart and

worshipped his mother, allowing her great political influence in the affairs of

state which she grasped eagerly, being a shrewd political operator. Her second ‘reign’

began in 1560 when her son Francis died. As her second son, Charles IX, was

only ten years old, Catherine became regent and virtually sovereign. She

displayed great political skill and diplomacy in her dealings with Protestant

England, under Elizabeth I, Catholic Spain under Phillip II (who was her

son-in-law), and the Huguenots within her own borders who were demanding a

state within a state. Catherine persisted in her policy of moving back and

forth between the Huguenot, English Protestant and Catholic positions refusing

to ally herself with one or the other. When Charles IX attained his majority,

he told his mother she should have even more power, but the fragile alliances

were falling apart. Catherine was frightened that the young king, inclined to

the Huguenot cause, would create problems with Spain and she gave the order for

the murder of one of the leading Huguenot statesmen in order to deflect her son

from such a course.

Tragically, Charles IX died aged only 25 in 1574 and her

third son, Henry Duke of Anjou became King of France. He was a much more

independent man than his two brothers and the influence of Catherine fell very

rapidly It was at this time that Catherine’s flirtation with the sect of the

flagellants became a matter of public record and one can surmise that a

powerful woman suddenly deprived of influence might need some alternative

source of spiritual guidance and direction. To the consternation of many, including

her son, she found it with the Black Brotherhood, a flagellant sect which, in

late 1574, marched through Avignon with Catherine at its head.

Her power slipping away, Catherine’s private behaviour

began to reflect her newly found public obsession. Dark stories began to

circulate around the Palace that Catherine had begun to physically chastise her

errant female staff and that one lady’s maid, who had apparently been caught

trying on a dress belonging to the now Queen Mother was whipped with birch rods

until her bottom bled copiously. This became a regular pattern of behaviour

during the latter part of her life and there were few maidservants who survived

a week without severe stripes across their buttocks. The least blemish in

behaviour by any of her maidservants, a soiled bedsheet, dust in the corners,

breakfast brought late, all punished by the poor girl stripping naked for a

sound dose of the rod before being allowed tearfully and painfully to resume

her duties.

Catherine began to preach the gospel of flagellation and

corporal punishment both as an instrument of restored religious values and as a

necessary domestic correction. She attempted to persuade her son to restore the

flagellant sect to a position of influence within the country but Henry was

outraged and would have none of it. So she compensated by practising on her

staff at every given opportunity.

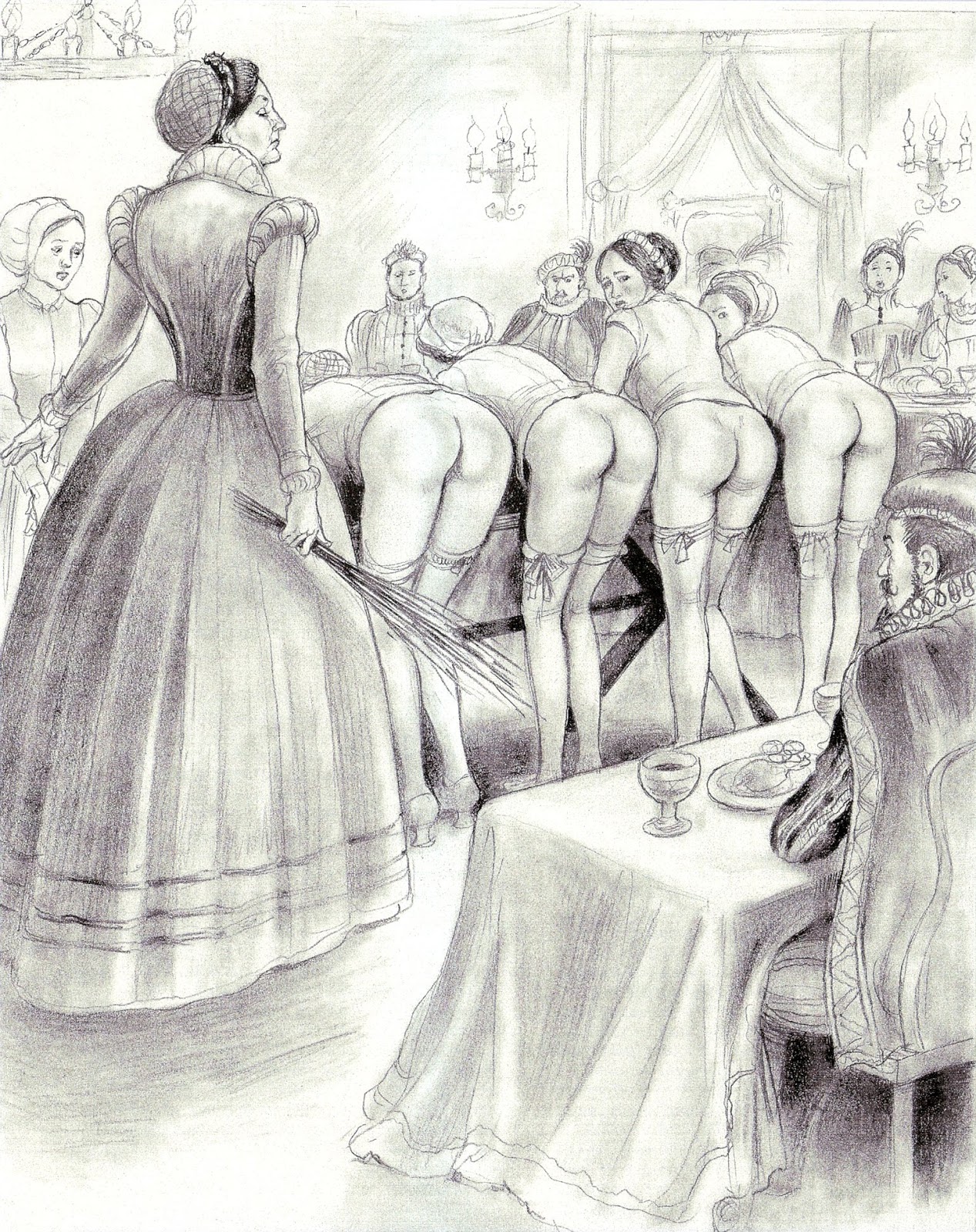

Perhaps the most notorious of Catherine’s excesses

followed a violent outburst of anger when she overheard four of her

ladies-in-waiting making fun of her irritability and increasingly eccentric

behaviour. These were not common serving maids but themselves ladies of the

nobility for whom serving the Queen Mother was a stepping stone to finding a

husband of some wealth and influence. What followed therefore must have been as

humiliating an experience as it was possible to bear. Catherine hosted a dinner

party for a number of influential members of the nobility during which the four

young ladies-in-waiting were summoned into the room. To the surprise, and in

most cases, severe embarrassment of the mainly male guests the unfortunate

ladies-in-waiting were naked from the waist down and made to stand in front of

the guests while Catherine delivered a public condemnation of their behaviour.

Then, in front of the assembled gathering, the four young women were bent over

a table and birched personally by Catherine until their screams rang round the

hall. Such was the disgust felt by many of the onlookers that Henry III felt

obliged to warn his mother that no such behaviour on her part would ever be

tolerated again, and it seems she heeded his warning.

Meanwhile, Henry III had fallen into bad company and

allowed his reign to fall into disrepute. He had no children and Catherine, now

growing old and bitter, saw her fourth child Francis of Valois die in 1584

leaving the future of France to Henry of Bourbon, a Protestant. All that

Catherine had worked for was falling apart before her eyes, yet she was still

politically astute enough to try to save Henry III from his own bad judgements.

Still desperate to keep traditional alliances intact, Catherine was in despair

when she found out that Henry had murdered his arch-rival the Duke of Guise.

Old, bitter and totally disillusioned, Catherine died on 5th January 1589, only

13 days after hearing this news.

Catherine de Medici was a fascinating mixture of wife,

mother, peacemaker, diplomat, tyrant and sadist. Ostensibly clever, historians

have judged that far from securing the future of France, her devious and

unscrupulous alliances which may have looked shrewd at the time actually sowed

the seeds of long term instability and distrust in France which took many years

to overcome.

Comments

Post a Comment